Compassion as Wisdom in Action, Part 2: The Nature of Suffering

SPECIAL SERIES: Distinguishing true compassion from emotional overwhelm and reclaiming its roots in wisdom.

This post continues a three-part special series exploring compassion as wisdom in action. Part 2 compares Western and Buddhist views, focusing on the nature of suffering as central to the Buddhist view of compassion.

In an age of chronic distraction, disconnection, and emotional fatigue, especially in the workplace, compassion is no longer a luxury for the spiritually inclined. It has become a critical capacity for clarity, connection, and human sanity.

Yet in contemporary Western culture, the distinct nature of compassion is often obscured: blurred with empathy, diluted by sentiment, or reduced to emotional reactivity and conflict avoidance.

By contrast, in many Eastern traditions—particularly Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism—compassion is understood not as a fleeting feeling or moral obligation, but as the natural movement of wisdom in action.

Part 1 of this three-part series examined the conflation of compassion and empathy, revealing that true compassion is rooted in wisdom rather than emotional resonance.

Part 2 unfolds in three sections:

Section 1 contrasts Western and Buddhist views of compassion, framing a fuller view of compassion as an expression of bodhicitta—the awakened heart–mind that arises from egoless, spacious awareness.

Section 2 explores compassion as a natural response to suffering, focusing on the Buddhist understanding of dukkha as central to its view of liberation.

Section 3 challenges the modern myth of “compassion fatigue,” reframing it through the lens of wisdom and discerning presence.

Section 1: Western vs. Buddhist Compassion

This section explores how Western and Buddhist traditions understand compassion—contrasting the action-oriented, often dualistic framing in the West with the non-dual awareness that grounds Buddhist compassion through the awakened heart–mind, or citta.

In Western psychology, compassion is typically defined as concern for another’s suffering, accompanied by a motivation to help. It often emphasizes external action and is closely linked to altruism, moral obligation, or social responsibility. While sincere, this approach can lack a deeper understanding of the roots of suffering and the role of awareness in responding to it.

As a result, compassion is frequently reduced to an emotional response, disconnected from inner wisdom. Western models also tend to overlook the presence cultivated through mindfulness—a presence that connects us to our shared humanity and supports grounded responsiveness.

Self-Compassion

Without the cultivation of non-dual awareness, compassion in the West remains subtly split—self versus other, giver versus receiver. This dualism quietly reinforces the very separation that deepens suffering.

To counterbalance this, Western approaches increasingly emphasizes self-compassion as a needed complement. Kristin Neff, a leading researcher on self-compassion, defines it as treating oneself with the same kindness and care offered to a good friend in distress. She notes it is not indulgence, but “a healthier alternative to self-esteem,” rooted in kindness rather than judgment or positive reinforcement.

By establishing healthy boundaries, self-compassion supports both inner stability and the capacity to offer authentic compassion to others. Yet as commonly framed, it often remains tethered to dualistic assumptions—personalizing suffering, separating one’s pain from others’, and reducing the practice to surface-level notions of “self-care.”

To move beyond this division, Buddhist traditions invite us into a deeper view—where compassion is not split between self and other, but arises naturally from non-dual awareness, as the spontaneous expression of an awakened, loving mind.

The Loving Mind: Bodhicitta

In Buddhist psychology, the mind is not merely cognitive or conceptual. The term citta refers to the heart–mind—the integrated seat of awareness, emotion, and intention. It is not just the source of thought, but also the root of compassion, clarity, and wisdom (prajñā).

Unlike the Western tendency to divide self from other—heart from mind, emotion from reason—Buddhism recognizes no such split. The awakened mind, or bodhicitta, is not intellectual in nature. As Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh puts it, “the loving mind sees clearly and responds with care.”

Buddhism views the self, body, and mind as interdependent processes. Feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness shape and influence one another moment by moment. The illusion of separation—between mind and heart, self and other—is the root of dukkha, the constriction that gives rise to suffering. Compassion arises naturally as this illusion softens and the loving mind returns to its innate clarity and spaciousness.

This loving mind integrates three dimensions often divided in Western psychology: the thinking mind, the feeling mind, and the habitual or subconscious mind. Western research suggests that the habitual mind governs up to 95% of our thoughts and reactions. Only a pliable and spacious awareness can hold all three—especially the unpredictable impulses of the habitual mind—with clarity and care.

Demonstrating this spacious compassion often involves the wisdom of pausing, attuning to the body, recognizing our limits, breathing deeply, and looking intimately into what’s present—whether that means offering restraint or asking honest, discerning questions. This deeper understanding opens the way to connection and learning.

Buddhist Compassion (Karuṇā)

Author and teacher Tsoknyi Rinpoche emphasizes this loving mind in his teachings. He points out that true compassion arises from realizing emptiness—not as a void but as a vast, open awareness free from fixation.

This softening of our hearts is essential for all progress, and not just in terms of spiritual practice. In all we do, we need to have an attitude that is open-minded and flexible … to have the compassionate attitude of wanting to help all sentient beings.

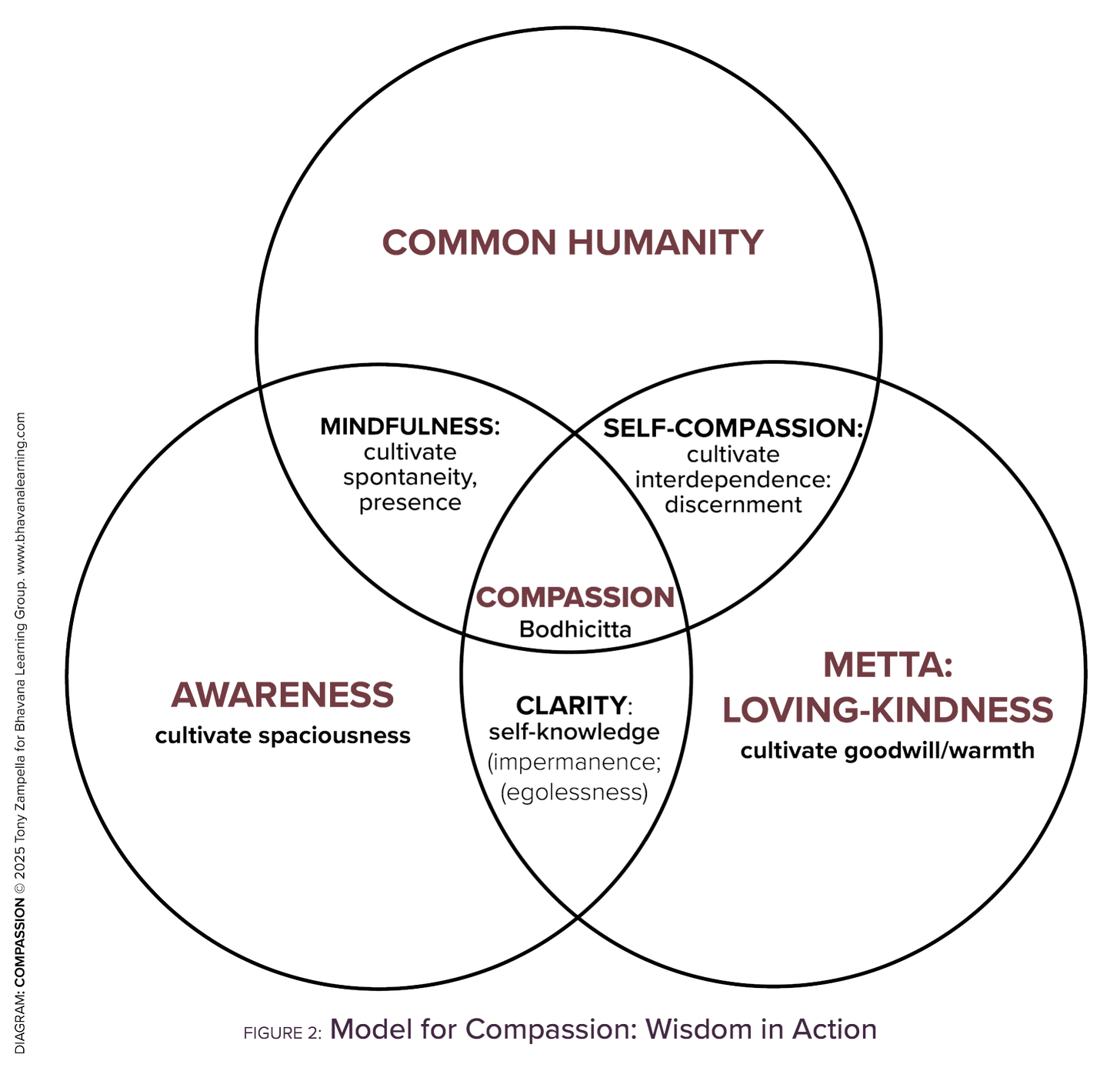

Buddhist compassion is the spontaneous response of the awakened heart–mind. Rooted in non-dual awareness, Buddhist compassion is non-attached, non-reactive, and non-transactional. It is grounded in presence, interdependence, and egolessness (see Fig. 2 below). This kind of compassion is not something one does for others—it is what naturally emerges when the illusion of separateness dissolves.

From a Western perspective, this spaciousness can seem cold or detached. However, this reflects a cultural misunderstanding. Non-attachment is not indifference. It does not mean avoiding or disconnecting from experience—it means meeting life fully without grasping, resistance, or identification. This makes space for compassion to arise without depletion.

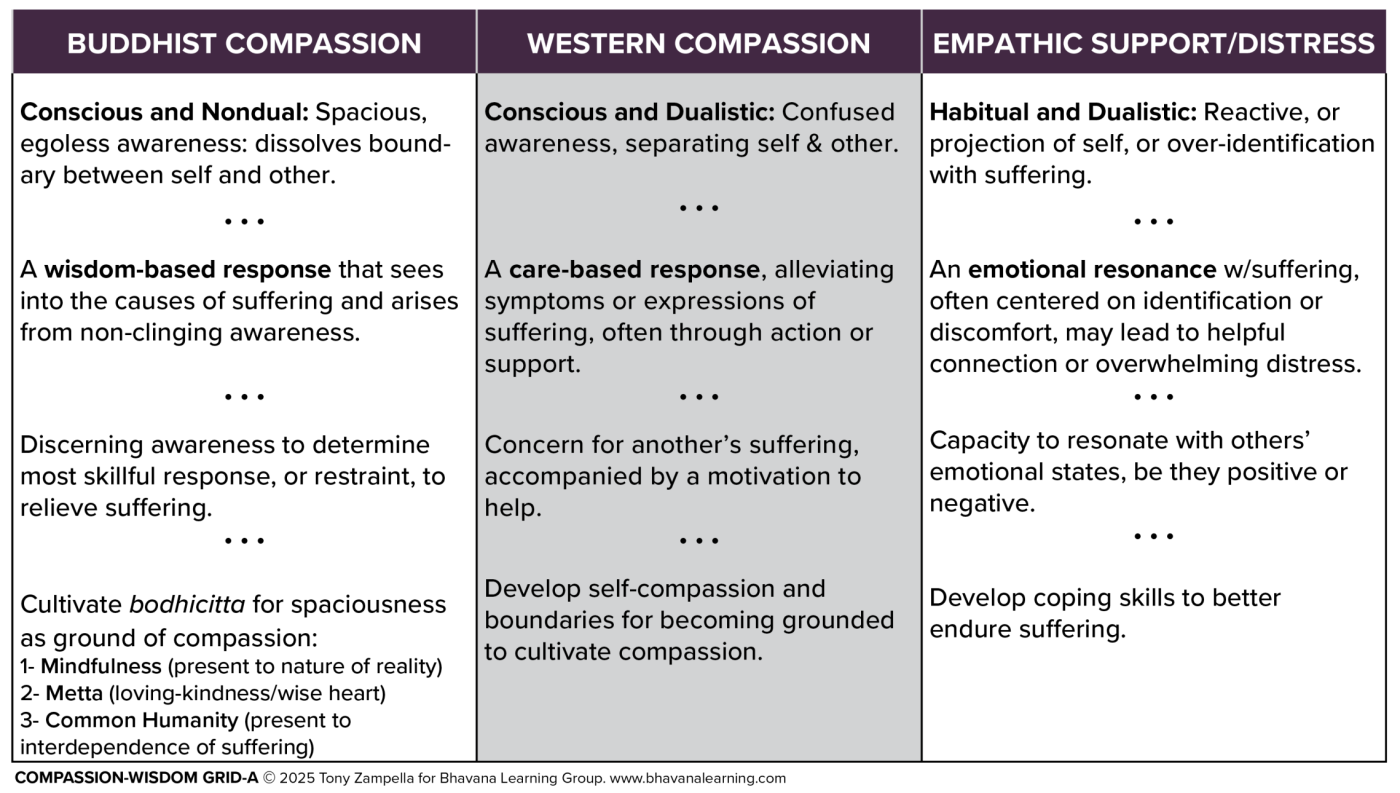

This distinction between Western compassion, Buddhist compassion, and empathic support brings us to the heart of the matter: how we understand and relate to suffering itself (see Grid A. below).

Buddhist Compassion: A wisdom-based response that sees into the causes of suffering and arises from non-clinging awareness.

Western Compassion: A care-based response aimed at alleviating the symptoms or expressions of suffering, often through action or support.

Empathic Support/Distress: An emotional resonance with suffering, often centered on identification or personal discomfort, which may lead to helpful connection or overwhelming distress.

To fully grasp the depth of Buddhist compassion, we must explore the nature of dukkha, as described in The Four Noble Truths, and how non-dual awareness transforms our relationship to it.

Section 2: Dukkha: The Suffering That Calls Forth Compassion

At the heart of Buddhist psychology lies the recognition of dukkha, the crowded, constricted space experienced as suffering, which arises from clinging, aversion, and identification. Dukkha is not just physical or emotional pain but the deeper unease of grasping and separation.

To fully understand Buddhist compassion, we must turn to what it responds to—not just pain, but the deeper structure of suffering, or dukkha. In this view, compassion is not merely a reaction to discomfort in others; it is the natural response of wisdom to the presence of dukkha in ourselves and the world around us.

In his guide to the Abhidharma—a systematic analysis of mind and reality in Buddhist psychology—Steven Goodman writes:

Prajna allows us to blast through this sense of self, the cause of our sufferings. We should be clear that this sense of self is not some minor aspect of our life but rather a term for the tightly, crowded, confused, and anxious patterns [dukkha] which make up my life.

Here, suffering (dukkha) is not just personal—it is perceptual. It arises from the illusion of a fixed, separate self navigating a world of otherness. As long as this illusion remains unexamined, even empathy or care can become reactive: merging with another’s pain, avoiding what that pain stirs in us, or trying to fix something in order to ease our own discomfort.

When suffering is met from this self-reference, even well-meaning empathy can collapse into empathic distress—a kind of burnout or emotional overwhelm that originates not from too much compassion but from a lack of spacious awareness. Boundaries blur, clarity fades, and our efforts to help entangle with the very confusion we hoped to relieve.

Non-Dual Awareness: Dissolving the Roots of Suffering

In contrast, compassion arises from non-dual awareness, a glimpse of spaciousness that flows from egolessness (Fig. 2 above). From the open, awakened heart–mind, we recognize the spacious moment that softens the constricting, grasping nature of dukkha. It is not born of projection, identification, or reactivity, but of clarity and presence. It sees suffering—including the crowded, constricted unease of dukkha—without becoming entangled in it. And in seeing it clearly, it loosens its grip.

Compassion does not merge with pain—it meets it. It does not collapse into emotional urgency but rests in discernment. It does not arise from a need to help but from a natural movement of wisdom and care.

A compassionate person is not trying to be good or fix anything. They are simply present: open to suffering, attuned to their roots, and responsive to what is needed. Unlike empathy, which remains tethered to the self, compassion is fueled by wisdom that sees no fixed self—only interdependence, moment by moment.

In summary, incorporating a non-dual view from the Buddhist tradition highlights the depth and clarity of genuine compassion. Empathy allows us to feel or imagine what others are experiencing, but it often filters suffering through our conditioning. Compassion, however, arises from spacious awareness. It sees dukkha for what it is and dissolves it not by avoiding, grasping, or fixing but through presence, clarity, and love.

Section 3: The Myth of Compassion Fatigue

The term compassion fatigue, often used among healthcare workers, caregivers, and those in helping professions, is frequently misunderstood.

Much of what is described as compassion fatigue is, in fact, a combination of overload, workload fatigue, burnout, empathetic overidentification (empathetic distress), and emotional exhaustion. At its core, it is not compassion that fatigues but empathic distress—a self-oriented, emotionally reactive state in which another’s suffering overwhelms one.

Emerging research in social neuroscience supports this distinction. Dr. Tania Singer at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences has demonstrated that empathy, not compassion, leads to emotional fatigue, particularly in caregiving professions (see research on veterinarians).

When caregivers emotionally merge (over-identify) with another’s pain without sufficient awareness or spaciousness, they lack inner clarity and discernment, risking depletion, disengagement, or collapse.

Beyond the Western tendency to reduce empathy and compassion to similar emotional states lie two very different human capacities.

Beyond the Western tendency to reduce empathy and compassion to similar emotional states exist two fundamentally different human capacities—each with its own ground and function. This may explain why Christine Comaford spent a week discussing compassion with the Dalai Lama without hearing a single mention of empathy.

Wisdom Is an Endless Source

True compassion arises from a different source. Rooted in wisdom, it is not reactive or entangled. It flows from egoless, spacious awareness—one that clearly sees the constriction of dukkha and meets it without clinging, avoidance, or over-identification. Rather than being drained by suffering, compassion holds it with clarity and care. It neither collapses into overwhelm nor flees discomfort.

In the Mahayana tradition, the practice of dāna—or generosity—offers a powerful model of this kind of compassionate engagement. Dāna involves giving and receiving freely, without attachment or expectation. Grounded in non-clinging awareness, it reflects the open mind–heart that offers itself without seeking anything in return. This differs sharply from the transactional view of generosity, expecting mutual benefit, exchange, or affirmation.

Like dāna, true compassion is inexhaustible. It does not grasp, perform, or drain. It flows—clear, steady, and warm—because it arises from the spaciousness of wisdom, not from the contraction of space or ego clinging.

Even self-compassion is often misunderstood in this context. While the practice is valuable, healing, and necessary, the concept can still reinforce a subtle dualism—a self offering kindness to the clinging self. However, true compassion ultimately transcends this split. It is not “for” oneself or “for” another. It is simply what arises when the nature of suffering is seen without illusion.

Closing Reflections—the Ground of Compassion

In Buddhist traditions, compassion is not a feeling we generate—it is the natural response that arises when the illusion of separateness softens. When suffering—dukkha—is seen clearly, without grasping or aversion, compassion moves like a wave from the still ocean of awareness. This is not sentimentality or self-sacrifice. It is wisdom in action.

As we've seen, the Western framing of compassion often centers empathy, emotion, or obligation—tethered to the self. But without a clear view of the nature of suffering, these models risk becoming reactive or depleting.

Compassion fatigue, for example, is not caused by compassion, but by empathic over-identification and emotional entanglement. True compassion, arising from non-clinging awareness, does not exhaust—it liberates.

By reframing compassion as the movement of bodhicitta—the awakened heart—we reconnect with its true source: not performance, but presence. Not effort, but emptiness.

In Part 3, we’ll turn to the modern distortions of Buddhist compassion—how niceness can enable dysfunction, how care can become performance, and how compassion itself can be fierce. We will discover how wise compassion reclaims its depth through discernment, boundaries, and unwavering clarity.

Reading Time: 9.5 min. Digest Time: 12.5 min.

1- VIEW OUR RELATED RESOURCES & BLOGS:

Compassion as Wisdom in Action, Part 1: Beyond Empathy

Part 1: A Multimedia Package: Beyond Empathy

Compassion as Wisdom in Action, Part 3: The Path to Common Humanity

I’m Tony V. Zampella —a teacher, wisdom coach, and leadership development consultant. I support accomplished professionals in turning a corner: expanding their inner lives to align with deeper purpose, presence, and impact.

My work blends Buddhist psychology with philosophical inquiry to support contemplative learning: reflective, embodied practices that cultivate awareness, presence, and meaning in both personal and professional life.

Contact Tony at Bhavana Learning Group

As I read this I couldn't help but think about my time working in health systems - this section about suffering in that "it arises from the illusion of a fixed, separate self navigating a world of otherness." And that when "unexamined, even empathy or care can become reactive: merging with another’s pain, avoiding what that pain stirs in us, or trying to fix something in order to ease our own discomfort."

I can remember so often being at the bedside with a nurse that I was training and hearing their recommendations for patients change depending upon the case managers level of comfort with the care needs of the patient. Often they over identified or over-fixated on something that they likely needed to release in their own life. This merge often caused more suffering and less room for true care for the patient.

Every hospital staff person needs to read this piece. Thank you.