Compassion as Wisdom in Action, Part 1: Beyond Empathy

SPECIAL SERIES: Distinguishing true compassion from emotional overwhelm and reclaiming its roots in wisdom.

This post begins a three-part series exploring compassion as wisdom in action. Part 1, clarifies how compassion differs from empathy, and why that distinction matters deeply in both personal and professional life.

Jane sat slumped in the hallway, her scrubs stained and her eyes glassy. “I used to care,” she whispered, “but now I just want to quit.” After years as a trauma nurse, Jane’s empathy had turned into exhaustion. She felt everything—every family’s panic, every patient’s grief—but she no longer had the space to respond skillfully.

“Is this what compassion fatigue is?” Jane asked. What she didn’t know was that it wasn’t compassion that had drained her—it was empathy without spaciousness. It was care without clarity. What Jane was missing wasn’t more emotional fuel—it was wisdom.

In an era marked by chronic distraction, social disconnection, and emotional distress—especially in the workplace—compassion is no longer a luxury for the spiritually inclined, but a critical capacity for clarity, connection, and human sanity.

Yet in contemporary Western culture, compassion is often diluted, sentimentalized, or confused with empathy. It is sometimes equated with emotional overwhelm or conflict avoidance.

The Question of Compassion

I first heard the phrase “compassion is wisdom in action” in 2005 from John Daido Loori, then abbot of the Zen monastery where I lived for a month-long immersion. He offered it during a teaching on the nature—and confusion—of compassion. The phrase struck me as intuitively true, although I couldn’t explain why.

In time, I came to see how Zen teachings often sidestep the rational mind. I understood that wisdom and compassion were considered essential virtues and that their integration was held as the highest expression of Buddhist virtue. Nonetheless, I was left with a lingering question: What does unwise compassion look like?

That question has stayed with me. I brushed against it again in 2018 when I wrote a blog exploring the differences between compassion, sympathy, and empathy. That post remains the most-read piece I’ve written, but in hindsight, I realize I avoided the deeper issue: the central role of wisdom in compassion.

Then, just last year, I received an invitation from a coach training network to attend the webinar titled, “Compassion: Empathy in Action.” The title stopped me cold. The phrase sounded polished and convincing but also deeply misguided. It collapsed two important capacities—empathy and compassion—while ignoring the central role of wisdom.

This three-part essay is my attempt to clarify that question.

Compassion is a full expression of our humanity—a spontaneous movement of wisdom (seeing) that awakens deep presence (being), responding naturally to relieve suffering (doing).

An Invitation

Since writing my original blog on compassion in 2018, I’ve noticed a growing interest in compassion, empathy, and what’s commonly called “compassion fatigue.” In the years shaped by the COVID pandemic, both scientific research and lived experience have deepened our inquiry—but have also exposed significant confusion. The essence of compassion remains as vital as ever, yet often vaguely understood.

In this three-part series, I return to a central question: What is compassion, and how does it differ from other human faculties?

Drawing from Buddhist psychology, Eastern wisdom traditions, and contemporary scientific studies, I explore key distinctions: how compassion diverges from empathy, how it is framed in Western versus Buddhist contexts, and how it can be misunderstood—even distorted—in modern culture.

Each part offers a space for reflection—an invitation to move beyond assumptions and into a fuller, more grounded understanding.

Part 1 explores the distinction between compassion and empathy, illuminating how true compassion is rooted not in emotional resonance, but in wisdom.

Part 2 examines both Western and Buddhist views of compassion, turning toward the nature of suffering—dukkha—as central to the Buddhist understanding.

Part 3 addresses common distortions of Buddhist compassion, offering a fuller view of compassion as wisdom in action.

If this series succeeds, I hope it reveals a broader view:

Compassion is a full expression of our humanity—a spontaneous movement of wisdom (seeing) that awakens deep presence (being), responding naturally to relieve suffering (doing).

The Question of Wisdom in Compassion

Although compassion is widely invoked, it is often misunderstood and frequently conflated with emotion, sentimentality, or moral obligation. To reclaim its deeper meaning, we move beyond these surface interpretations and draw from Eastern wisdom traditions, where compassion is not merely a feeling or response, but wisdom in action.

At the heart of this view is the relationship between wisdom, spaciousness, and compassion. I offer the following definitions to frame this inquiry:

Wisdom is a direct, intuitive knowing, held within the spacious clarity of non-clinging awareness. It reveals how our fixed perceptions give rise to suffering—and gently loosens their grip.

Spaciousness ripens as ego-clinging softens our attachment to fixed identity, outcomes, and roles. From this openness, the heart of compassion naturally emerges.

Compassion arises from the warm, spacious, and awakened heart—the loving mind (citta) of this awareness. It is the sincere impulse to relieve suffering—not through reaction or performance, but through presence, clarity, and care.

A Metaphor for Integration

Wisdom is like a vast, clear ocean—deep, still, and spacious.

Compassion is the wave that rises when suffering touches its surface.

The wave is not separate from the ocean; it is the ocean in motion.

This form of compassion is grounded in wisdom—the insight of shunyata, or emptiness—not as nihilism, but as the clear recognition of the interdependent and impermanent nature of all things. It is not effortful or moralistic, but spontaneous: an awakened response to the reality of suffering.

Untangling the Confusion

The Latin root of the word compassio (com, “with” + passio, “suffering”) literally means “to suffer with.” While this etymology is evocative, it can be misleading. In modern usage, compassion is often reduced to the following:

Sentimentality—Feeling bad for someone (akin to sympathy) and acting to soothe our own discomfort rather than engaging the deeper roots of their suffering with discernment.

Emotional Impulse—A response driven by empathy or emotional resonance, where the boundary between the self and the other dissolves without insight into the nature or causes of suffering. This often leads to emotional contagion rather than clarity.

Moral Obligation—A value-driven action rooted in duty or principle. While moral obligation is often virtuous, it may lack the depth of awareness needed to perceive suffering through the lens of interdependence and non-duality.

Even intellectual reasoning, sometimes mistaken for wisdom, can fall short. While analytical or systems thinking may produce effective outcomes, it often lacks warmth, presence, and a felt sense of shared humanity. True wisdom is not abstract or detached; it is embodied, intuitive, and clear.

According to this deeper view, wisdom is not just conceptual understanding; it is direct, non-clinging awareness that sees suffering and its causes clearly, and loosens the grip of our conditioned perceptions. From that spacious clarity arises karuṇā—compassion—not as sentiment or performance but as the spontaneous expression of the awakened heart.

To access this deeper dimension of compassion, we must learn to distinguish it from its more familiar but ultimately limiting counterparts.

Empathy vs. Compassion

The source of and motivation for compassion are rarely examined in Western definitions, leading to confusion about what compassion is and is not. This section explores some of that confusion, beginning with the role of empathy and how it is often mistaken for compassion.

Although empathy is a valuable human capacity, it differs from compassion. Contemporary research identifies two primary forms of empathy:

Affective Empathy involves sympathetic concern to feel what others feel. It can promote prosocial behavior, inhibit aggression, and support moral sensitivity.

Cognitive Empathy refers to the ability to imagine another’s perspective or internal state to understand what one might be thinking, feeling, or experiencing.

Both forms allow us to resonate with another’s emotional or cognitive world. Whether through shared feelings or imagined perspectives, empathy is interpersonal and grounded in the self’s recognition of its experience reflected in the other.

But this very identification reveals a central limitation: Empathy often centers on the self. It filters the other’s experience through our own conditioning. In her article “The Neuroscience of Empathy, and Why Compassion Is Better,” Christine Comaford calls this the “Me Bias,” because “it makes us unconsciously more sympathetic toward individuals we think are similar to us.”

In this way, empathy often becomes a subtle projection of the self’s solidity—its preferences, biases, and unresolved wounds—onto the suffering of others. While it may appear to bridge the gap between the self and other, it can unintentionally reinforce the illusion of separation.

In her article in Psychology Today, Veronika Tait, Ph.D., frames empathy as “susceptible to in-group bias, [and a] compassion meditation seeks to expand one’s in-group.” Tait shares this grid to distinguish between empathy and compassion.

The “Self” in Empathic Distress

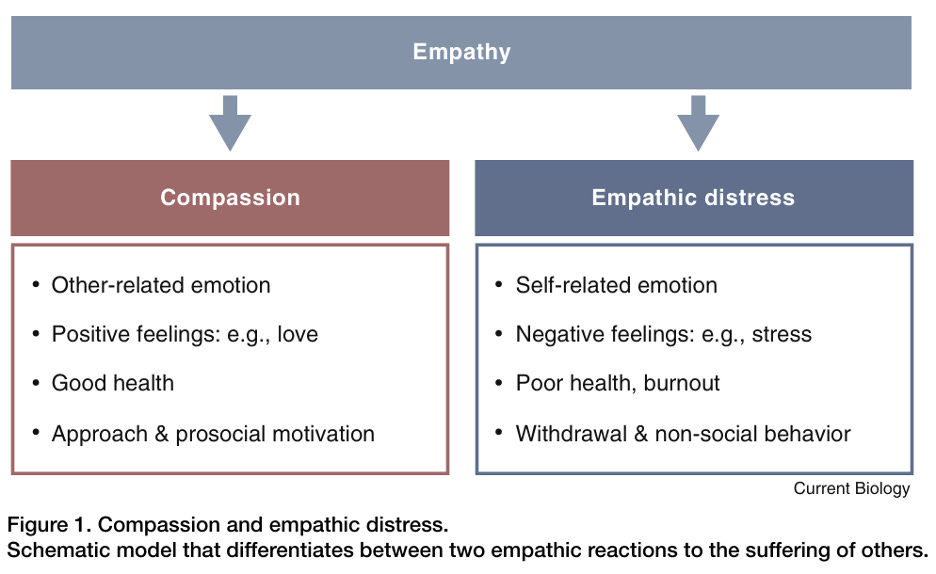

Western scientific research, while helpful, often remains confined to a dualistic framework. It focuses on the emotional or behavioral responses of either the self or the other, as in the illustration (see Fig. 1 above), and as follows:

Empathy is the capacity to resonate with others’ emotional states, be they positive or negative.

Empathic Distress is an aversive, self-oriented response to another’s suffering, often accompanied by a desire to withdraw.

This framing misses something essential: It largely ignores the role of the self’s own suffering and how unexamined suffering through conditioning shapes the very way we relate to the suffering of others.

The following examples demonstrate the distinction between empathy distress and compassion as distinguished and developed in this series.

Empathy with Distress

Maria is a nurse working long hours in a pediatric oncology unit. One afternoon, she enters the room of a young patient in visible pain and sees the child’s parents in tears. Her heart aches. She imagines what it would be like if this were her own child—and immediately feels overwhelmed. She tries to console the family, but her voice shakes. She avoids eye contact and wants to escape the room. Her distress intensifies, not from the child’s pain alone, but from her emotional identification with it. Later, she feels exhausted, guilty, and depleted. She wonders how long she can keep doing this work.

Maria is experiencing empathetic distress: Her resonance with suffering is filtered through her own emotional lens. She’s caught in dukkha, clinging to her projections and overwhelmed by the collapse of boundaries. Her intention to help is sincere, but her response is reactive and tangled in identification.

Compassion with Spacious Awareness

Elena, another nurse in the same unit, walks into a similar scene. She feels the heaviness in the room, but she doesn’t immediately internalize it. She takes a breath, softens her body, and grounds herself. She listens fully. She gently places a hand on the parent’s shoulder and offers a calm, reassuring presence. She doesn’t rush to fix the moment or ease her discomfort; she stays steady, open, and present. She helps coordinate support for the family and later leaves the room with a soft ache in her chest, as well as clarity and peace.

Elena responds with compassion: Her awareness is spacious and grounded. She feels the reality of suffering but without grasping or avoidance. Her response arises not from emotional reactivity but from clarity, presence, and care. Her capacity to hold suffering without collapsing into it reflects wisdom in action.

In sum, Maria and Elena reveal two radically different responses to suffering. Maria's empathy, filtered through identification and unexamined pain, leads to overwhelm and burnout. Elena’s compassion, grounded in presence and wisdom, allows her to remain open without being consumed. One collapses into suffering; the other meets it with clarity.

This contrast reveals that compassion is not merely intensified empathy—it is a distinct capacity, rooted in non-clinging awareness and a different view of self and suffering (explored further in part 2). In this space, we respond not from reactivity, but from wisdom.

Closing Reflections—the Ground Beyond Empathy

Distinguishing compassion from empathy, sentimentality, and obligation allows us to reclaim its deeper nature: a spontaneous, embodied response to suffering that arises from interdependence and non-clinging awareness.

While empathy, informed by separation, often centers the self through emotional resonance, compassion, grounded in interdependence, dissolves that boundary. It moves us from identifying with suffering—seeing the other through the lens of our own experience—to being fully present with suffering, without merging (attachment) or distancing (detachment).

This shift invites us into a different way of seeing: a non-dual awareness where the illusion of separateness softens, and presence itself becomes the ground from which true compassion flows.

In part 2 of this series (next week), I will examine both Western and Buddhist views of compassion, turning toward the nature of suffering—dukkha—as central to the Buddhist understanding.

We’ll examine how dukkha arises from the illusion of a fixed, separate self, and how true compassion emerges from the spaciousness that meets this suffering without clinging or aversion. This view exposes the widespread myth of “compassion fatigue” for what it is: not the cost of caring, but the consequence of empathic entanglement.

Reading Time: 9.5 min. Digest Time: 12.5 min.

1- VIEW OUR RELATED RESOURCES & BLOGS:

Part 1: A Multimedia Package: Beyond Empathy

Compassion as Wisdom in Action, Part 2: The Nature of Suffering

Compassion as Wisdom in Action, Part 3: The Path to Common Humanity

Rethinking Boundaries: An Ontological View from Protective to Presence

I’m Tony V. Zampella —a teacher, wisdom coach, and leadership development consultant. I support accomplished professionals in turning a corner: expanding their inner lives to align with deeper purpose, presence, and impact.

My work blends Buddhist psychology with philosophical inquiry to support contemplative learning: reflective, embodied practices that cultivate awareness, presence, and meaning in both personal and professional life.

Contact Tony at Bhavana Learning Group

I feel deep gratitude for the clarity Tony provided in understanding Compassion & Empathy. I honed my empathetic practices to a high level from the time I was a young child living with an emotional distraught mother. This continued until I had suicidal thoughts after attending a memorial service for a woman who committed suicide. At that moment I realized I needed to learn how not to "take on" the emotions of others; to be different around them. That difference is the way Tony defines Compassion. It is a lifelong journey to discover & hone True Wisdom.